Julia's latency: Past, present and future

Written 2023-03-31, updated 2023-05-05

One of the most annoying features of Julia is its latency: The laggy unresponsiveness of Julia after starting up and loading packages.

Latency is a major user experience issue that is apparent right away, and shapes the first impressions people have of the language, so naturally, it's a common complaint when the Internet discusses Julia. In the same threads, you find responses along the lines of:

Latency a high priority for the core developers, and being worked on. It has already dropped by an order of magnitude since 1.0, and will continue to drop in the future. If you haven't given Julia a try for years, it should be much better now

But what exactly has happened since Julia v1.0? Has latency really dropped by a factor of 10? And what exactly is planned for the future?

In this post, I'll give a brief history of Julia's latency, discuss its current status, and speculate on future work to reduce latency further. This post is meant both for potential Julia users curious about the language, but who wants to wait until latency is better before they begin using it, and for current Julia users who are out of the loop about developments in latency and wants to catch up.

If you're impatient, you can skip to a graph summarizing efforts so far.

- The past: How we got here

- The pre-1.5 era: Not much happens

- The first obvious step: Cache more code

- A brief primer of Julia code caching

- A brief primer on invalidations

- Invalidations and uninferability

- Reducing invalidations: v1.5 - v1.7

- PrecompileTools.jl: v1.8

- Caching external codeinstances: v1.8

- Package images: v1.9

- Other latency efforts

- Impact of efforts so far

- v1.9 is much faster

- Not much happened from v1.4 to v1.7

- The present: Where are we now?

- The future: Where is the latency heading?

The past: How we got here

The pre-1.5 era: Not much happens

Before Julia 1.5, reducing latency was not a top priority for the core developers. Of course, as a major usability problem experienced by daily users, latency did receive some attention, and latency-reducing PRs were made.

But back before v1.5, there were other priorities. Pre v1.0, focus was obviously on getting the semantics and API of the language right, since that would be set in stone with the release of 1.0. After 1.0, attention turned towards areas of the language where it was deemed that not fleshing them out quickly could cause long-term problems for the language. For example, the package manager needed to support federated package registries and move away from relying on GitHub, and Julia's multithreading API had to be established.

As a result, nothing much happened regarding latency from around 2017 (where I learned the language) until the spring of 2020. Most of the features that was deemed time critical did land between Julia 1.0-1.4, after which the developers turned a large part of their attention to reducing latency.

The first obvious step: Cache more code

The first, most promising avenue to dramatically reduce latency caused by compilation was to cache more code. It was believed that in any given session, users would only need to (re)define a tiny fraction of the total amount of compiled code, and therefore only should need to compile a tiny fraction of the code and could theoretically load the rest from a cache serialised to disk.

Since Julia v1.0 (and before), Julia already has two distinct mechanisms for caching code: Code compiled during a session was cached in memory, and code compiled during package installation was cached to disk in a process known as precompilation. However, these two caching mechanisms were severely limited in the pre-1.5 period. To properly explain the issues, it's worth taking a detour to get an overview of the code caching systems in Julia.

A brief primer of Julia code caching

The main purpose of Julia is to be fast, dynamic and interactive at the same time. To achieve this, it's designed as a thoroughly compiled language that allows dynamic redefinition of methods. Suppose you define the following functions

f(x::Int) = x * 5

g(x) = f(first(x))The function f has a single method f(::Int), whereas the function g has the single method g(::Any). Julia methods are generic over all their arguments, so the method g(x::Any) is generic over x.

When you then call a function, e.g. by calling g([5]):

julia> g([5])

25This is what happens:

First, the matching method among all the methods of

gis found. The details of how this happens is is not relevant here, you can learn about this elsewhere.Second, the found method, here,

g(::Any)is monomorphized to a methodinstance. That means the compiler creates a non-generic methodinstanceg(::Vector{Int})out of the generic methodg(x::Any)by looking at the actual, concrete types of the arguments at runtime (namelyVector{Int}).Then, after the code has been monomorphized, and the methodinstance compiled, the methodinstance is called and its value returned. Since the methodinstance is not generic but only contains concrete types, the compiler is able to generate efficient code despite Julia being dynamic. In this case, it just returns a literal

25.

Invoking the compiler at every function call would be totally unworkable, so this scheme only works due to two important optimisations: First, every methodinstance is cached in memory. When the method g(::Any) is called, e.g. as g([5]), Julia looks up in the cache whether a methodinstance with the signature g(::Vector{Int}) exists. If not, it compiles the methodinstance and saves it to cache. If it does, it simply fetches the compiled code and executes it.

Second, since the compiler statically knows that g(::Vector{Int}) will call f(::Int), Julia first compiles f(::Int) before g(::Vector{Int}), then statically inserts the function call to f into g. So, when f is called from g, there is no need to look f up in the cache. Essentially, when the compiler knows at compile time what methods it needs to call, it behaves like a normal static language, with all the performance gains that come from that.

Besides caching already-compiled methodinstances in memory, packages may also precompile some of their methods. The idea here is that if a package defines some method foo, the method might as well be compiled when the package in installed. The compiled code can be serialised to disk, then loaded when the user loads the package, similar to a normal static language.

In the pre-1.5 era, both types of caching had significant limitations that needed to be lifted to improve caching, and hence latency. The main problem was that there was widespread cache invalidation: A large fraction of methods were being compiled and stored in the cache, only to then be cleared from the cache and re-compiled. It was believed that addressing invalidations was the most important first step: By reducing invalidations, less code had to be recompiled, leading to easy latency wins. Furthermore, any other optimisations to the cache would be defeated if most of the cached code had to be invalidated anyway.

Thus, after the release of Julia 1.4, the developers and especially Timothy Holy, started hunting down invalidations.

A brief primer on invalidations

As shown above, Julia 1) caches compiled methodinstances in memory, and 2) is, like other compiled languages, able to insert static callsites and inline functions.

Unfortunately, these two optimisations conflict somewhat with having a dynamic, interactive language. For example, if I define the functions f and g as above, I can then redefine f - and g must still work[1] :

julia> f(x::Int) = x + 1;

julia> g([5])

6However, since the call to f was inlined into g, this means redefining f must also cause g to be recompiled. This works by having a backedge from all methodinstances to all of its callers - in this case, from f(::Int) to g(::Vector{Int}). Redefining a method will invalidate the cache entry for all of that method's methodinstances, which then invalidates all the methodinstances pointed to by their backedges, which in turn invalidates all the methodsinstances pointed to by those methodinstances' backedges, and so on.

Thus, when a method is redefined, a large number of methodinstances may need to be re-compiled, including sometimes methodinstances in the Julia language, package manager, or compiler itself, leading to latency.

Luckily, people actually rarely redefine existing methods. Doing so essentially redefines existing behaviour, which other code may rely on, potentially causing correctness problems. Julians have coined the term type piracy for this nasty behaviour, and it is considered faux pas: An author may extend functions they defined themselves with new methods, or they may extend other people's functions with methods whose signature contain types they defined themselves. But defining a method for a function in someone else's code, using only someone else's types is frowned upon as "type piracy".

Incidentally, this is analogous to Rust's "orphan rule" - except that Rust's compiler makes it impossible to break the orphan rule, whereas in Julia, we acknowledge that it may occasionally be convenient to commit type piracy (say, between two packages under the same project), and so we merely advise you against doing it.

Type piracy can lead to massive cache invalidations, but it's fortunately rare, so it does not account for the large-scale invalidations prior to Julia 1.5. To understand those, we have to look at how Julia deals with uninferable code, that is, code where the compiler doesn't know the types of all variables.

Invalidations and uninferability

Because Julia is supposed to be expressive, high-level, dynamic and interactive, it's an absolute non-starter to require Julia code to be completely inferable, as static languages require. It must be possible to run, and therefore compile, code where the compiler does not know all types, and so the Julia compiler is designed to handle a kind of "gradual typing", where only partial type information is known.

Of course, with only partial type information, the compiler is limited in its optimisations, and must produce code that is slower and which checks all unknown types at runtime. Nonetheless, it has been a focus for the Julia developers to create a compiler that can produce reasonably fast code even with limited type information.

Let's look at an example. Suppose I have the same definitions as above:

f(x::Int) = x * 5

g(x) = f(first(x))But now, this time, I call the method g(::Any) with an un-typed container: g(Any[5]). Now, the compiler has no information about the type of first(x). The Julia IR created by the compiler for the methodinstance g(::Vector{Any}) is:

julia> @code_typed g(Any[5])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ %1 = Base.arrayref(true, x, 1)::Any

│ %2 = (isa)(%1, Int64)::Bool

└── goto #3 if not %2

2 ─ %4 = π (%1, Int64)

│ %5 = Base.mul_int(%4, 5)::Int64

└── goto #4

3 ─ %7 = Main.f(%1)::Int64

└── goto #4

4 ┄ %9 = φ (#2 => %5, #3 => %7)::Int64

└── return %9

) => Int64This is Julia IR, which might be a little hard to read, but the code is equivalent to:

y = x[1]

if y isa Int

y*5

else

typeassert(Int, f(y))

endI.e. Julia can't predict the type of y = x[1] - it infers it to be of type Any. However, it knows f(y) is the next step, and f is only (so far) defined as f(::Int), therefore it checks if y is an Int and if so, returns y*5 (having inlined f(::Int)). If not, it calls f(y) in order to throw a MethodError.

So: The compiler managed to emit efficient code even with no type information about the argument to f - good job! Unfortunately, it means that now, the code of g is only correct if there is only that one method of f - defining a new method of f, without committing type piracy, will invalidate g. For example, if I define:

f(::Float64) = 1.0Then g will be invalidated, because it needs to be re-compiled to:

y = x[1]::Any

if y isa Int

y*5

elseif y isa Float64

1.0

else

f(y)::Union{Float64, Int}

endAnd here we come to the crux of the matter: Uninferable code is vulnerable to being invalidated simply by defining new methods. When loading packages, with hundreds of new method definitions, thousands of methodinstances may be invalidated, each of which must be re-compiled. The very optimisations that the compiler uses to regain performance when running poorly inferred code are the same causing large scale cache invalidations and blocking any improvements to Julia's code caching.

Reducing invalidations: v1.5 - v1.7

A major goal, therefore of Julia 1.5 and 1.6, was to reduce the amount of code cache invalidations.

A big part of the effort went into developing tooling to measure Julia's compiler in order to gain a better understanding of the details of the problem: The packages SnoopCompile.jl, MethodAnalysis.jl, Cthulhu.jl and JET.jl were all created, or received much attention, during this period.

The compiler itself was also improved to reduce invalidations: PR 36733 refined the invalidation algorithm, thereby exempting some methods that didn't need invalidation from being so. PRs 36208 and 35904 limited the aggressiveness of the optimisations that tries to regain performance from poorly-inferred code, which, as we saw above, could lead to invalidations.

However, most of the improvements between Julia 1.5-1.7, came from simply fixing uninferable code in Base Julia - all packages rely on Base, so invalidations of Base code had by far the worst impact on latency. Among other people, Tim Holy made a flurry of PRs between Julia 1.5 and 1.7 to improve inference of Base.

The job of reducing invalidations by improving inference continues to this day, although all the truly awful cases have been fixed by now. In the words of Tim Holy, the invalidations we hunt now are like geckos, compared to the dinosaurs that used to stomp around before Julia 1.6.

The reduction of invalidations between v1.5 and 1.7 directly improved latency, but perhaps more importantly paved the way for improving precompilation.

PrecompileTools.jl: v1.8

One major problem with precompiling code during package installation time is that all Julia methods are generic over all their arguments. Hence, if I create a package where I define a method foo(a, b, c), there is no way for the compiler, only based on the method definition, to know which methodinstance(s) I would want to compile from the method.

Before v1.8, package authors could add precompilation statements of the form:

precompile(foo, (MyType, Int, String))to cache the methodinstance foo(::MyType, ::Int, ::String). Unfortunately, creating these statements and copy-pasting them into your code were a pain in the butt, and so very few package authors bothered to do so. This changed with Julia 1.8, when the package PrecompileTools.jl (originally called SnoopPrecompile.jl) was released. With it, authors simply need to create a block of code, that uses functionality from the package, and wrap it in a @compile_workload macro. When running the macro, PrecompileTools will record all methods being compiled during execution of the code, and automatically emit precompilation statements for these during package installation time. Even cooler, this only happens during package installation: During normal package loading, the entire PrecompileTools codeblock will be compiled to a no-op, thus contributing minimally to latency itself.

For example, a user could add this to their package:

@compile_workload begin

subjects = load_data("test/file.csv")

results = full_analysis(subjects)

[ more statement ]

endand all functions called by any function inside the block would be precompiled. This way, PrecompileTools made precompilation so easy that any package author who cares about latency can precompile much of their code. As of April 2023, PrecompileTools has 148 direct dependents, a number that I very much hope will continue to grow in the future.

Caching external codeinstances: v1.8

Before Julia 1.8, a large fraction of methodinstances could not be compiled, even if precompile statements were generated for them. The reason was that packages could only save code that "belonged" to the package itself, i.e. methodinstances for which either the function, or one of the arguments were defined in the package. If package A imported function f from package X and type T from package Y, then called f(::T), that methodinstance did not belong to package A, and was therefore not eligible for precompilation[2].

PR 43990 enabled packages to also cache "external codeinstances", namely code defined in other packages. This, in theory, enabled caching of essentially all function calls. The combination of this PR with PrecompileTools made precompilation far more widespread and was the reason for the observed drop in latency many packages experienced from Julia 1.7 to Julia 1.8.

Package images: v1.9

Another major issue with precompilation was that only a small part of the whole compilation pipeline could be precompiled. Briefly, Julia's compiler process code in several steps:

First, Julia source code is lowered to... well, lowered code, the highest level of Julia IR, with a fairly straightforward correspondence to source code. This always happens at precompile time to all source code, such that raw source code is never loaded from disk.

Then, type inference is run on the lowered code. This is the step that requires monomorphization, and therefore a precompile statement (or a PrecompileTools block) in order to determine the concrete methodinstances to compile.

Third, Julia's front-end compiler will optimise the lowered code using the usual compiler tricks such as inlining, loop hoisting etc into fairly low-level Julia-like code. With the changes in v1.8, practically all code up to and including this level could be cached.

Finally, Julia emits LLVM code from its IR, and calls into LLVM to produce machine code from that.

Prior to Julia 1.9, the native code from this last step could not be cached to disk during precompilation. LLVM is famously slow, so not the uncacheability of this bottleneck was a major restriction of precompilation. This changed with PR 44527 and PR 47184, such that in v1.9, the result of all steps of the compiler can be cached during precompilation.

Hence, from version 1.9, all code can be cached, and theoretically, no code actually needs to be compiled by the user (though in practice, users probably wants to define and compile some new methods themselves). The last major step in the long process of improving code caching was complete.

Other latency efforts

In 1.6, precompilation was parallelised. This only sped up package installation time (which I do not consider "latency" in this article), but in doing so incentivized developers to move more work to precompile time, so is worth mentioning.

PR 43852 and many follow-up PRs upgraded the compiler's reasoning about side effects from Julia 1.8 onwards, allowing the compiler to use the faster constant evaluation instead of constant folding/propagation.

PR 45276 in Julia 1.9 makes the compiler scale better with the length of functions. This only really matters for packages that uses huge functions, typically programmatically generated functions.

PR 47695 in Julia 1.9 added package extensions, which allow users to extend code from other packages without having them as dependencies. It is still to early to tell the impact of this PR, but it could potentially significantly lower the number of dependencies of packages throughout the ecosystem, thereby indirectly lower latency.

Impact of efforts so far

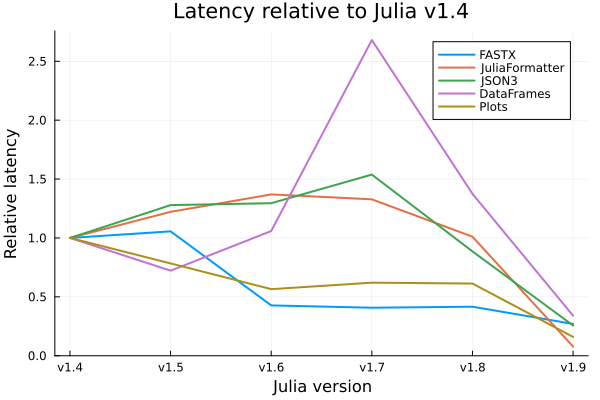

So: How much have all these initiatives mattered? To check it, I made five different latency-heavy workloads, and tested them on 6 different versions of Julia. Since the packages themselves develop over time, often in response to the evolution of Julia, I created virtual environments for each package/version pair, such that e.g. when timing Plots on Julia 1.4, the entire environment only uses Julia packages with the versions available at the time of Julia 1.4.

Different packages are affected differently

The first thing to notice is that the development of latency across time differs massively by workload. Plots.jl is doing well and getting faster most releases - but this is not surprising. Plots.jl has become the posterboy for latency, and has become the unofficial latency benchmark for the Julia developers. Indeed, latency is often referred to as "time to first plot". New latency-related PRs are usually gauged by measuring their impact on Plots.jl, so regressions in Plots.jl would be quickly discovered. So, Plots.jl does better most Julia releases because Julia has become optimised for running Plots.jl. We also see FASTX.jl mostly improving. This package is particularly "well behaved": It's thoroughly inferable, does not commit type piracy, and much of its heavy lifting happens during precompilation. In contrast, DataFrames' latency bizarrely more-than-doubled from v1.4 to v1.7, and was still ~40% slower in v1.8 than in v1.4. JSON3 and JuliaFormatter are more typical - they largely get slower from v1.4 to v1.7, but then get faster again in v1.8 and 1.9.

v1.9 is much faster

The next to notice is that huge strides has been made in Julia 1.9. All workloads are by far fastest in this latest release. Compared to v1.4, the latency is between 3 and 13 times lower - in absolute terms, it dropped from 11 seconds to 0.9 seconds for JuliaFormatter and from 19 to 3 seconds for Plots, whereas DataFrames "only" dropped from 9 to 3 seconds, and FASTX from 2.6 to 0.7 seconds.

Not much happened from v1.4 to v1.7

This was the most surprising finding to me - Julia v1.6 was widely considered a quantum leap in terms of latency, and there has been a continuous stream of smaller latency-focused PRs since v1.6 not mentioned in this blog post. Yet in the plot, for three of the five workloads, Julia v1.7 is worse than Julia v1.4. Why are the fruits of these efforts not visible in the plot - indeed, why does it get worse?

One explanation could be that I just picked particularly unlucky packages. Anecdotally, some packages like SIMD.jl and LoopVectorization.jl experienced massive improvements when invalidations were reduced in Julia 1.6, but I happened to not pick any using these packages for my test. However, I don't think the packages I chose are particularly unlucky - certainly not Plots.jl or FASTX.jl - and besides, the improvements to latency are widely assumed to apply to packages generally, not just select packages.

Another factor could be that latency improvements are matched one-for-one with regressions introduced by new compiler capabilities. Since Julia v1.4, the compiler has gotten significantly smarter and will, among other things, constant-fold/evaluate much more aggressively, elide boundschecks automatically if safe, and generally infer better. It is well known that, without a concerted effort to retain compiler speed, it tends to regress over time as they accumulate more features. This has famously happened to LLVM, the compiler backend used by Julia. I personally think the new compiler improvements are awesome and worth the latency, but it's worth thinking about the cost.

Perhaps more importantly, packages tend to get larger over time. From 1.4 to 1.9, DataFrames.jl doubled from 11k to 22k lines of code, exclusive dependencies which increased from 17 to 23. In the same span, Plots.jl went from 26 to 36 dependencies (although cutting about 15% of its lines of code). There is something almost profound about how, due to Julia's package manager being so great, it is almost too easy to add new dependencies, a situation which has been remarked on with Rust's Cargo.

It's worth noting that these dynamics may warp the language developers' understanding of how much progress they are making. From their point of view, they are merging PR after PR showing significant latency improvements (for Plots.jl), for years on end. Surely, they might think, latency must have dropped significantly after all those PRs? Yet, my data shows differently. This is probably why some Julia developers in various ways on various forums have been saying that latency has been reduced "by an order of magnitude", even before 1.8 - when in fact, many, perhaps most, packages saw latency getting worse and worse.

The present: Where are we now?

The most impactful changes so far has been about allowing package authors to precompile more of their their packages. With package images in v1.9, precompilation has been massively improved and is in the grand scheme of things done, enabling speedups that are actually an order of magnitude.

But the keyword here is enabling - the efforts only bear fruit if package authors exploit them. We've already seen many packages get serious about precompilation but I believe latency in the package ecosystem is currently far worse than what Julia makes possible, and we could all have significantly lower latency if we only made use of the advances that has been made.

So - how do you do make your package precompilable as an author? The good news is that the same steps that reduce latency and enable precompilation are also things that improve the general code quality of your package. Hence, as a package author, you should see it less as "fiddling with your code to make the compiler happy" and more as "cleaning up the package before release". In fact, I've come to believe that most packages should not optimise latency directly, and huge strides can be made if package authors simply follow a few guidelines about general code quality:

1: Do not commit type piracy

Don't get in the habit of committing type piracy. Not only for latency reasons, mainly because redefining other people's code is terrible practice and leads to correctness issues. If you feel type piracy is necessary, it typically means you need to refactor your packages, or need to make a PR upstream to one of your dependencies.

The package Aqua.jl (Automatic QUality Assurance of packages) can statically find piracy and can be integrated in your test suite and CI. In general, Aqua.jl includes a lot of nice functionality to make your package better.

2: Write inferable code

Get in the habit of writing inferable code. If you're uncertain if, or why, a function is uninferable, use @code_warntype, or, preferably, the more featureful @descend from Cthulhu.jl's to investigate. Inferable code is faster at runtime - also after compilation - it is more debuggable, behaves more predictable and can be analysed statically. Don't worry - writing inferable code by default quickly becomes a habit. In fact, I would argue that building the habit of writing inferable code makes you a better programmer.

If you have a larger codebase which is uninferable, you can use VSCode's profiler to profile a workload and detect all calls where dynamic dispatch happens. Alternatively, you can use JET.jl on your PrecompileTools workload to detect dynamic dispatch in your code and fix it.

Strive to have near zero dynamic dispatch for your workload - usually, writing idiomatic Julia code will be enough to do that. For tasks that are inherently type unstable, like parsing JSON, you can add typeasserts to limit the scope of type instability.

3: Remove unimportant dependencies

It's common to see packages take on dependencies for trivial tasks. Ask yourself if you really need them - remember that dependencies not only add latency, they are also a source of potential bugs, installation issues and upgrade deadlock.

You also see packages add dependencies, not because they need them, but simply to allow interoperability with them. For example, suppose I write a package that defines my_function. The package does not depend on the popular OtherType type from OtherPackage.jl, but for users who do use OtherPackage.jl, it's convenient to have defined my_function(::OtherType), so therefore I add OtherPackage.jl to my dependencies. This allows me to have this great new feature, but all users, even those who do not care about interoperability with OtherPackage.jl now bears its latency.

With Julia 1.9, it's possible to have modules that are conditionally loaded when specific packages are in your environment - so called "package extensions". Hence, you could define a package extension that defines my_function(::OtherType) ONLY when OtherPackage is loaded, but where OtherPackage is not a dependency of your package.

Finally, many packages include dependencies that are only used when developing or testing the package, such as Test, BenchmarkTools or JuliaFormatter. Don't make your users pay for the latency of loading these packages at runtime - add them in dedicated testing and development environments.

4: Use PrecompileTools

Add PrecompileTools as a dependency and execute a representative workload which exercises the main functionality of your package in top-level scope of your package:

@compile_workload begin

x = MyHugeType("abc")

modify!(x)

[ ... ]

endIn general, you want your workload to eventually end up calling all the functions you want to precompile. For advanced users, you can use SnoopCompile.jl to determine which methods are compiled at runtime and therefore perhaps should be part of the workload - but as a package author, you probably have a pretty good idea about the main functionality of your own package.

Adding a PrecompileTools workload is the only latency-reducing measure you need to take which is specifically latency-reducing, and does not improve the overall code quality. Luckily, it's quick and easy to do.

The future: Where is the latency heading?

The immediate future is easy to predict, because the same things that has been happening for years will continue to happen: Some of the exciting recent advances will be cancelled out by new compiler regressions due to fancy new compiler features. We users will create still deeper code stacks that racks up latency, even more so with Julia 1.9 now that latency has improved and we can "afford" to do so.

On the other hand, I'm also optimistic that Julia 1.9 may change some user behaviour for the better. In the old days, optimising your package for latency sometimes meant jumping through hoops to optimise for obscure compiler internals, all for limited gain. Now, latency can be reduced manyfold by simply implementing bog-standard code quality improvements and a PrecompileTools workload. Today, you also have tooling like JET.jl, Aqua.jl and the VSCode profiler to make it easier. This both lowers the barrier to, and increases the incentive to write inferable, precompilable packages, compared to just a few years ago. I'm hopeful that more package authors will adopt these practises, and the resulting improvements to latency will propagate through the ecosystem.

However, there are also more work to do on the Julia development side, which will presumably happen slowly over the next several years:

Optimise package loading

Loading packages have traditionally been slow for two reasons: First, the package loading itself (i.e, loading all the defined methods and types), and second, the compilation of new methods, or old methods invalidated by the newly loaded code.

The recent changes to invalidations and code caching has massively improved the latter, but code loading itself is only moderately faster today than 2 years ago. Hence, while the total DataFrames workload latency decreased from 9 to 3 seconds, loading only decreased from 2.0 to 1.6 seconds, and thus went from ~20% to ~50% of total time. For the JuliaFormatter workload, loading time actually increased by 50% from 0.4 to 0.6 seconds, even as total latency dropped from 11 to 0.9 seconds, such that loading went from 1/25th of the latency to 2/3rds!

With most attention so far having been put on compilation, not loading, there are presumably some low-hanging fruits in code loading, and it's an obvious next target for latency improvements. The Julia devs are pretty confident that code loading itself can be made faster than it already is in v1.9, and I'm guessing it will be improved significantly "soon" - so, probably, over the next releases, 1.10 or 1.11.

Parallel compilation

Julia's compiler is mostly single-threaded, although select parts of it, such as precompilation, happen in parallel. Adding more parallelism is an obvious area of improvement, indeed, it's slightly ironic that a language with such easy multithreading as Julia doesn't itself have a multithreaded compiler. The last year or so, the developer Prem Chintalapudi has been laying groundwork to introduce more parallelism. Most recently, PR 47797 parallelised system image building, adding more parallelism to precompilation. There is still some way to go until Julia's compiler can use multiple threads for compilation during a session or script, but it is on the horizon, meaning it will hopefully land over the next few years.

Compile to static libraries or binaries

Julia already compile to machine code - it just compiled directly in the memory of your computer. Then why can't it compile the same code to binaries or libraries? Indeed, there is nothing fundamental in Julia preventing this - it simply hasn't been implemented yet.

There has already been some foundational work to enable this. PR 41936 allowed separating the codegen part from the Julia runtime, allowing you to start run Julia without the compiler. The Julia devs have also hinted that more foundational work is happening. The package StaticCompiler.jl already now is able to produce small executables from Julia code - but it is experimental and brittle at this stage.

I'm not aware of any concrete plans to implement this, so I think it's safe to assume this is still very hypothetical, and probably won't happen for the next several years. I certainly wouldn't hold my breath waiting for it.

Compile-on-demand

In general, Julia will compile functions when they are called - except in the case where it statically knows function g calls function f. Then, it will compile f when also compiling g.

Usually, this is what you want - if f will be called anyway during the execution of g, you might as well compile it when you compile g. However, some code paths may not be taken in any particular session, meaning some functions that are statically identified may never need to be compiled.

LLVM has functionality for this "compile on demand", and Prem Chintalapudi is working on it currently.

Hybrid compiler/interpreter

More speculatively, the developers have talked about executing Julia using an interpreter, then compiling the same code in a background thread, and switching execution from the interpreted version to the compiled version when the compiled version is done.

This is pretty tricky for Julia in particular: The language has come to depend on an efficient compiler to produce code with any reasonable runtime performance. Primarily because Julia is mostly implemented in Julia, all the way down to low-level integer operations, running Julia through an interpreter adds way more overhead than for e.g. Python, whose interpreter can simply offload all the low-level stuff to Python's internals written in C. Also, idiomatic Julia tends to be written in a way that makes use of copious zero-cost abstractions, expecting their cost to be compiled away before runtime. Hence, a Julia interpreter is massively slower than even Python, and would need serious performance overhauls and some clever design before it would be suitable as the go-to code executor. So, a hybrid compiler/interpreter is at the moment highly speculative optimisation, and as far as I know, no actual work has been done in this area so far, so if this optimisation ever lands, it will take many years.

More tooling improvements?

This is sort of a joker, because tooling to allow developers to reduce latency has already improved quite a lot, and it's difficult as a user to put my finger on exactly what kind of tooling I'd like to see getting build. Nonetheless, I feel strongly that there could exist better tooling which would guide developers more easily towards writing low-latency code. This is a common user experience for all software: Users can easily tell that something isn't quite as nice as it could be, but can't articulate what it should be instead. Nonetheless, let me try:

It is currently still too difficult to automatically diagnose type piracy. Ideally, a package like Aqua should detect all instances of type piracy, and for each instance, explicitly tell you in which package the function and each argument is defined. Even more ideally, a piracy check should be an automatic part of the language server, such that your IDE will put a fat, red line under a method definition if it's a pirate.

While JET.jl makes it easy to detect inference problems, the output is not provided in a way that is particularly actionable: It does not display the call chain that leads to uninferability with all types, such that you can easily identify the function call where type information is lost, it does not flag abstractly typed containers, and there are still too many "false positives" from places like Base where users can't do anything about them. This is particularly true when you run

@report_opton a large, type unstable code base.

| [1] | Famously, this used to not work in Julia back before I learned the language: If a method was redefined (or even if a new, more applicable method was defined), any callers would not get updated, and would simply return the wrong answer. This was tracked in issue 265, possibly the most infamous issue ever in Julia, and solved five years later, in PR 17057 for Julia 0.6. |

| [2] | This is closely analogous to type piracy, but note that type piracy is about defining methods for foreign functions using foreign types, whereas "external codeinstances" (i.e. foreign methodinstances) are created when you simply call methods with such function signatures. Creating such foreign methodinstances is completely legitimate and must be expected in most packages. |